There are many communists who still live in denial mode about Stalin , they should try and

read some of his works starting with the Gulag Archipelago.

I recommend this only so that the mistakes of the past are not repeated.

An Interview with Alexander Solzhenitsyn some months before his death.

Half a century since they were published, Solzhenitsyn's searing accounts of Stalin's labour camps remain among the most profound works of modern literature. Last summer, as his health began to fail, he looked back on his extraordinary life with Christian Neef and Matthias Schepp

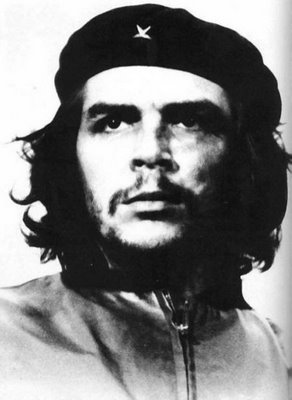

Nobel prize-winning author and critic of Soviet regimes Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn sitting on low stone wall outside his home

Q: Alexander Isayevich, when we came in we found you at work. It seems that even at the age of 88 you still feel this need to work, even though your health doesn't allow you to walk around your home. What do you derive your strength from?

Solzhenitsyn: I have always had that inner drive, since my birth. And I have always devoted myself gladly to work – to work and to the struggle.

Q: In your book My American Years, you recollect that you used to write even while walking in the forest.

Solzhenitsyn: When I was in the gulag I would sometimes even write on stone walls. I used to write on scraps of paper, then I memorised the contents and destroyed the scraps.

Q: And your strength did not leave you even in moments of desperation?

Solzhenitsyn: Yes. I would often think: whatever the outcome is going to be, let it be. And then things would turn out all right. It looks like some good came out of it.

Q: I am not sure you were of the same opinion when, in February 1945, you were arrested by the military secret service in Eastern Prussia. In your letters from the front, you were unflattering about Joseph Stalin, and the sentence for that was eight years in the prison camps.

Solzhenitsyn: It was south of Wormditt. We had just broken out of a German encirclement and were marching to Königsberg [now Kaliningrad] when I was arrested. I was always optimistic. And I held to and was guided by my views.

Q: What views?

Solzhenitsyn: Of course, my views developed in the course of time. But I have always believed in what I did and never acted against my conscience.

Q: All your life you have called on the authorities to repent for the millions of victims of the gulag and communist terror. Was this call really heard?

Solzhenitsyn: I have grown used to the fact that public repentance is the most unacceptable option for the modern politician.

Q: Putin [then President] says the collapse of the Soviet Union was the largest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century and that it is high time to stop this masochistic brooding over the past, especially since there are attempts "from outside", as he puts it, to provoke an unjustified remorse among Russians. Does this not just help those who want people to forget everything that took place during the county's Soviet past?

Solzhenitsyn: Well, there is growing concern all over the world as to how the United States will handle its new role as the world's only superpower, which it became as a result of geopolitical changes. As for "brooding over the past", alas, that conflation of "Soviet" and "Russian", against which I spoke so often in the 1970s, has not passed away in the West, or in the ex-socialist countries, or in the former Soviet republics. The elder political generation in communist countries was not ready for repentance, while the new generation is only too happy to voice grievances and level accusations, with present-day Moscow a convenient target. They behave as if they heroically liberated themselves and lead a new life now, while Moscow has remained communist. Nevertheless, I dare hope that this unhealthy phase will soon be over, that all the peoples who have lived through communism will understand that communism is to blame for the bitter pages of their history.

Q: Including the Russians.

Solzhenitsyn: If we could all take a sober look at our history, then we would no longer see this nostalgic attitude to the Soviet past that predominates now among the less affected part of our society. Nor would the Eastern European countries and former USSR republics feel the need to see in historical Russia the source of their misfortunes. One should not ascribe the evil deeds of individual leaders or political regimes to an innate fault of the Russian people and their country. One should not attribute this to the "sick psychology" of the Russians, as is often done in the West. All these regimes in Russia could only survive by imposing a bloody terror. We should clearly understand that only the voluntary and conscientious acceptance by a people of its guilt can ensure the healing of a nation. Unremitting reproaches from outside are counterproductive.

Q: To accept one's guilt presupposes that one has enough information about one's own past. However, historians are complaining that Moscow's archives are not as accessible now as they were in the 1990s.

Solzhenitsyn: It's a complicated issue. There is no doubt, however, that a revolution in archives took place in Russia over the past 20 years. Thousands of files have been opened; the researchers now have access to thousands of previously classified documents. Hundreds of monographs that make these documents public have already been published or are in preparation. Alongside the declassified documents of the 1990s, there were many others published which never went through the declassification process. Dmitri Volkogonov, the military historian, and Alexander Yakovlev, the ex-member of the Politburo – these people had enough influence and authority to get access to any files, and society is grateful to them for their valuable publications.

As for the last few years, no one has been able to bypass the declassification procedure. Unfortunately, this procedure takes longer than one would like. Nevertheless the files of the country's most important archives, the National Archives of the Russian Federation [GARF], are as accessible now as in the 1990s. The FSB sent 100,000 criminal-investigation materials to GARF in the late 1990s. These documents remain available for citizens and researchers. In 2004-2005 GARF published the seven-volume History of Stalin's Gulag. I co-operated with this publication and I can assure you that these volumes are as comprehensive and reliable as they can be. Researchers all over the world rely on this edition.

Q: About 90 years ago, Russia was shaken first by the February Revolution and then by the October Revolution. These events run like a leitmotif through your works. A few months ago you reiterated your thesis: Communism was not the result of the previous Russian political regime; the Bolshevik Revolution was made possible only by Kerensky's poor governance in 1917. If one follows this line of thinking, then Lenin was only an accidental person, who was only able to come to Russia and seize power here with German support. Have we understood you correctly?

Solzhenitsyn: No. Only an extraordinary person can turn opportunity into reality. Lenin and Trotsky were exceptionally nimble and vigorous politicians who managed in a short time to use the weakness of Kerensky's government. But allow me to correct you: the "October Revolution" is a myth generated by the winners, the Bolsheviks, and swallowed whole by progressive circles in the West. On 25 October 1917, a violent 24-hour coup d'état took place in Petrograd. It was brilliantly and thoroughly planned by Leon Trotsky – Lenin was in hiding to avoid being brought to justice for treason. What we call "the Russian Revolution of 1917" was the February Revolution.

The reasons driving this revolution do indeed have their source in Russia's pre-revolutionary condition, and I have never stated otherwise. The February Revolution had deep roots – I have shown that in The Red Wheel. First among these was the long-term mutual distrust between those in power and the educated society, a bitter distrust that rendered impossible any constructive solutions for the state. And the greatest responsibility falls on the authorities: who if not the captain is to blame for a shipwreck? So you may indeed say that the February Revolution in its causes was "the results of the previous Russian political regime".

But this does not mean that Lenin was "an accidental person" by any means; or that the financial participation of Emperor Wilhelm was inconsequential. There was nothing natural for Russia in the October Revolution. Rather, the revolution broke Russia's back. The Red Terror unleashed by its leaders, their willingness to drown Russia in blood, is the first and foremost proof of it.

Q: To paraphrase something you once said, the dark history of the 20th century had to be endured by Russia for the sake of mankind. Have the Russians learnt the lessons of the two revolutions and their consequences?

Solzhenitsyn: They are starting to. A great number of publications and movies on the history of the 20th century are evidence of a growing demand. Recently, the state TV channel Russia aired a series based on Varlam Shalamov's works, showing the terrible, cruel truth about Stalin's camps. It was not watered down.

And since February [2007] I have been surprised by the heated discussions that my now republished article on the February Revolution has provoked. I was pleased to see the wide range of opinions, since they demonstrate the eagerness to understand the past, without which there can be no meaningful future.

Q: How do you assess the period of Putin's governance in comparison with those of Yeltsin and Gorbachev?

Solzhenitsyn: Gorbachev's administration was amazingly politically naive, inexperienced and irresponsible towards the country. It was not governance, but a thoughtless renunciation of power. The admiration of the West only strengthened his conviction that his approach was right. But let us be clear that it was Gorbachev, and not Yeltsin, as is now being claimed, who first gave freedom of speech and movement to the citizens of our country.

Yeltsin's period was characterised by a no less irresponsible attitude to people's lives, but in other ways. In his haste to have private rather than state ownership as quickly as possible, Yeltsin started a mass, multi-billion-dollar fire sale of the national patrimony. Wanting to gain the support of regional leaders, Yeltsin called for separatism and passed laws that encouraged the collapse of the Russian state. This deprived Russia of its historical role for which it had worked so hard, and lowered its standing in the international community. All this met with even more hearty Western applause.

Putin inherited a ransacked and bewildered country, with a poor and demoralised people. And he started to do what was possible – a slow and gradual restoration. These efforts were not noticed, nor appreciated, immediately. In any case, one is hard pressed to find examples in history when steps by one country to restore its strength were met favourably by other governments.

Q: It has become clear that the stability of Russia is of benefit to the West. But one thing surprises us in particular: when speaking about the right form of statehood for Russia, you were always in favour of civil self- government, and you contrasted this model with Western democracy. After seven years of Putin's governance we can observe totally the opposite phenomenon: power is concentrated in the hands of the president, everything is oriented toward him.

Solzhenitsyn: Yes, I have always insisted on the need for local self-government for Russia, but I never opposed this model to Western democracy. On the contrary, I have tried to convince my fellow citizens by citing the examples of highly effective local self-government systems in Switzerland and New England.

In your question you confuse local self-government, which is possible on the most grassroots level only, when people know their elected officials, with the dominance of a few dozen regional governors, who during Yeltsin's period were only too happy to join the federal government in suppressing local self-government.

I continue to be extremely worried by the slow development of local self-government. But it has started. In Yeltsin's time, local self-government was barred, whereas the state's "vertical of power" (ie, Putin's top-down administration) is delegating more and more decisions to the local population. Unfortunately, this process is still not systematic in character.

Q: But there is hardy any opposition.

Solzhenitsyn: An opposition is necessary for the healthy development of any country. You can scarcely find anyone in opposition, except for the communists. However, when you say "there is nearly no opposition", you probably mean the democratic parties of the 1990s. But if you take an unbiased look at the situation, there was a rapid decline of living standards in the 1990s, which affected three quarters of Russian families, and all under the "democratic banner". Small wonder, then, that the population does not rally to this banner any more. And now the leaders of these parties cannot even agree on how to share portfolios in an illusory shadow government. It is regrettable that there is still no large-scale opposition in Russia. The growth and development of an opposition will take more time and experience.

Q: During our last interview you criticised the election rules for state Duma deputies, because only half of them were elected in their constituencies, whereas the other half, representatives of the political parties, were dominant. After the election reform made by Putin, there is no direct constituency at all. Is this not a step back?

Solzhenitsyn: Yes, it is a mistake. I am a consistent critic of "party-parliamentarism". I am for non-partisan elections of true people's representatives who are accountable to their districts, and who in case of unsatisfactory work can be recalled. I do understand and respect the formation of groups on economical, cooperative, territorial, educational, professional and industrial principles, but I see nothing organic in political parties. Politically motivated ties can be unstable and quite often they have selfish ulterior motives. Leon Trotsky said it accurately during the October Revolution: "A party that does not strive for the seizure of power is worth nothing." We are talking about seeking benefit for the party itself at the expense of the rest of the people. This can happen whether the takeover is peaceful or not. Voting for impersonal parties and their programmes is a false substitute for the only true way to elect people's representatives: voting by an actual person for an actual candidate. This is the point behind popular representation.

Q: In spite of high revenues from oil and gas, and the development of a middle class, there is a vast contrast between rich and poor in Russia. What can be done to improve the situation?

Solzhenitsyn: I think the gap between rich and poor is an extremely dangerous phenomenon and needs the immediate attention of the state. Although many fortunes were amassed in Yeltsin's times by ransacking, the only reasonable way to correct the situation is not to go after big businesses but to give breathing room to medium and small businesses. That means protecting citizens and small entrepreneurs from arbitrary rule and corruption.

Q: Recently, relations between Russia and the West have got somewhat colder. What is the reason? What are the West's difficulties in understanding modern Russia?

Solzhenitsyn: The most interesting [reasons] are psychological, ie, the clash of illusory hopes against reality. This happened both in Russia and in West. When I returned to Russia in 1994, the Western world and its states were practically being worshipped. This was caused not so much by real knowledge or a conscious choice, but by disgust with the Bolshevik regime and its anti-Western propaganda.

This mood started changing with the cruel Nato bombings of Serbia. All layers of Russian society were deeply and indelibly shocked by those bombings. The situation then became worse when Nato started to spread its influence and draw the ex-Soviet republics into its structure. This was especially painful in the case of Ukraine, a country whose closeness to Russia is defined by millions of family ties among our peoples, relatives living on different sides of the national border. At one stroke, these families could be torn apart by a new dividing line, the border of a military bloc.

So, the perception of the West as mostly a "knight of democracy" has been replaced with the disappointed belief that pragmatism, often cynical and selfish, lies at the core of Western policies. For many Russians it was a grave disillusion, a crushing of ideals. At the same time, the West was enjoying its victory after the Cold War, and observing the 15-year-long anarchy under Gorbachev and Yeltsin. It was easy to get accustomed to the idea that Russia had become almost a third world country and would remain so. When Russia started to regain some of its strength, the West's reaction – perhaps subconscious, based on erstwhile fears – was panic.

Q: The West associated it with the ex-superpower, the Soviet Union.

Solzhenitsyn: Which is too bad. But even before that, the West deluded itself – or maybe conveniently ignored the reality –by regarding Russia as a young democracy, whereas there was no democracy. Russia is not a democratic country yet; it is just starting to build democracy. It is all too easy to take Russia to task with a long list of omissions, violations and mistakes.

But did not Russia clearly and unambiguously stretch its helping hand to the West after 9/11? Only a psychological shortcoming, or else a disastrous shortsightedness, can explain the West's irrational refusal of this hand. No sooner did the US accept Russia's critically important aid in Afghanistan than it started making newer and newer demands. As for Europe, its claims towards Russia are fairly transparently based on fears about energy, unjustified fears.

Isn't it a luxury for the West to be pushing Russia aside now, especially in the face of new threats? In my last Western interview before I returned to Russia [for Forbes magazine in April 1994] I said: "One can see a time in the 21st century when both Europe and the US will be in dire need of Russia as an ally."

Q: What is, in your opinion, the situation in Russian literature today?

Solzhenitsyn: Periods of rapid and fundamental change were never favourable for literature. Significant works, have nearly always and everywhere been created in periods of stability, be it good or bad. Modern Russian literature is no exception. The educated reader today is much more interested in non-fiction. However, I believe that justice and conscience will not be cast to the four winds, but will remain in the foundations of Russian literature, so that it may be of service in brightening our spirit and enhancing our comprehension.

Q: In 1987 you said it was really hard for you to speak about religion in public. What does faith mean for you?

Solzhenitsyn: For me faith is the foundation and support of one's life.

Q: Are you afraid of death?

Solzhenitsyn: No. When I was young, the early death of my father cast a shadow over me – and I was afraid to die before all my literary plans came true. But between 30 and 40 years of age my attitude to death became quite calm and balanced. I feel it is a natural, but no means the final, milestone of one's existence.

Q: Anyhow, we wish you many years of creative life.

Solzhenitsyn: No, no. Don't. It's enough.

Independent

Tags: